[Source: CNN]

When Gustavo Petro, Colombia’s first progressive president, took office in August, he laid out an ambitious agenda.

His administration would finally achieve a stable peace with Colombia’s multiple rebel organizations; it would fight inequality by taxing the top 1% and lifting millions out of poverty; and it would abandon a punitive approach to drug policing that costed millions of lives around the world to little results, he promised.

Three months later, there are signs for optimism: Colombia and the largest rebel group still active in its territory, the National Liberation Army ELN, have signed a commitment to restart peace negotiations after a four years hiatus; and Congress has passed a fiscal plan that aims to collect almost 4 billion USD in new taxes next year.

But drugs remain perhaps the hardest challenge for Petro.

Drug production boomed in Colombia during the pandemic.

The total area harvested for coca leaves – the main ingredient for cocaine – grew 43% in 2021 according to a new annual survey by the United Nation’s Office on Drug and Crime. At the same time, the amount of potential coca produced per hectare grew a further 14%, the UN reported, leaving experts to believe Colombia is producing more cocaine than ever in its history.

In many rural parts of the country, the production of illicit drug became the only economic activity during pandemic lockdowns, the UN explains, as markets and agricultural routes shut down and farmers switched from food crops to coca.

According to Elizabeth Dickenson, a senior analyst at the International Crisis Group, the spike in harvests has become so evident even the casual traveler can see it.

“A few years ago, you’d have to drive for hours to see coca crops. Now they are much more common, less than one kilometer from the main highway,” she told CNN after a recent field trip to Cauca, part of a Colombian southwestern region that has seen a +76% increase in harvested area.

In the Indigenous reserve of Tacueyo, Cauca, the increase in coca and marijuana harvests have caused profound concern for the leaders of the community according to Nora Taquinas, an Indigenous environmental defender who has received multiple death threats from criminal organizations.

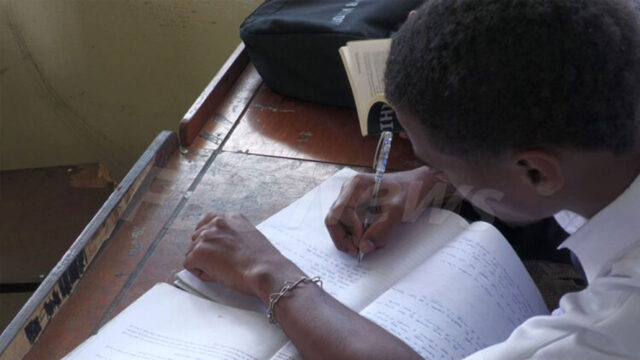

Two signs show a more sustained drug trade than in recent years, Taquinas says: informal checkpoints on the road leading up to Tacueyo and worrying trends of school dropouts as local children are pressed into service by criminal organizations for menial tasks around the production of narcotics.

“The cartels pay about 15’000COP (about 3USD) to clean a pound of marijuana sprouts. A kid can do up to six pounds per day, and that is solid money down here. It’s hard to stop that.”

The only positive aspect, Taquinas says, is that the increase in drug production and trade in her community has not caused higher levels of violence. “We are on the lookout. But soon enough, the cartels will start competing for the harvests here, and the competition between them is to the death. Right now, it’s like the calm before the storm.”

The proliferation of armed groups in recent years is one of the greatest shortcomings of the Colombian peace process, which in 2016 brought an end to more than half a century of civil warfare.

Before the deal, most of the guerrilla groups were disciplined like a regular army and this helped war negotiations between public officials and rebel groups. Now, the armed actors who didn’t abandon armed struggle have splintered in up to sixty different groups often in competition against themselves, according to the United Nations.

Even if the recently announced peace negotiation with the ELN succeeded, there are at least 59 more groups involved in the drug trade for the government to deal with.