[Source: CNN Entertainment]

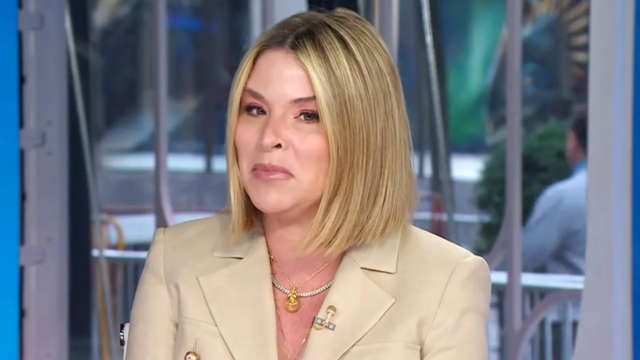

Ashley Judd feels the presence of her late mother in what she describes as “winks” or “small nudges.”

She has followed those gentle impulses to the greeting card aisle at Walgreens, where Judd will stop and look at the cards from mothers to daughters and pick out the one that her mom – singer and songwriter Naomi Judd – would have chosen for her.

“You know, I did that at Christmas. I do that on my birthday. And I pick out the one that I would have gotten for her, for the holidays,” Judd recalled in a recent conversation with CNN’s Anderson Cooper for his podcast “All There Is.”

Judd has done a lot of healing work in the more than 20 months since her mom died by suicide at age 76 in 2022.

“There is a place where trauma and grief and transcendence meet, and I call it the braid,” Judd explained. “I think that I’m grief literate now and grief and I are on pretty good terms. That doesn’t mean I get a pass. It doesn’t mean that there’s a shortcut, but there’s a shorthand.”

It’s a shorthand Judd has learned through the courage she has found to process pain she experienced in her childhood and in her mother’s passing.

“I think that the death of a parent is something for which we, at least conceptually, have some kind of preparation. I also knew that she was walking with mental illness and that her brain hurt and that she was suffering,” Judd told Cooper.

But that didn’t necessarily prepare her.

“My mother’s death was traumatic and unexpected because it was death by suicide, and I found her,” she said. “And, so, it had this calamitous dynamic, my grief was in lockstep with trauma.”

Judd said before she was able to begin grieving her mom, she had to address her trauma first.

“There’s a difference between trauma and grief. The trauma is intrusive and iterative, it comes up unbidden. We don’t have any control over it. It’s a memory that’s not processed and that lives free in the brain, bouncing around and seizes us and it needs to be stored properly in the brain,” Judd said. “Grief is a natural, organic human process that has natural stages that self-resolve over time.”

In the months immediately after her mother’s death, Judd sought support in eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy, an evidence-based treatment that can help reduce negative emotions associated with traumatic events.

“The truth is I had to work my ass off,” Judd said. “I just dragged my bones over there twice a week for three months just to work on my trauma.”

Judd said her grief followed.

“I actually had a re-experience of the shock, which is the first stage of grief, a year after my mama died. You know, I would just be doing something, washing the dishes, writing on my second book, and this wave of shock would overcome me, as if I had just walked in the room again.”

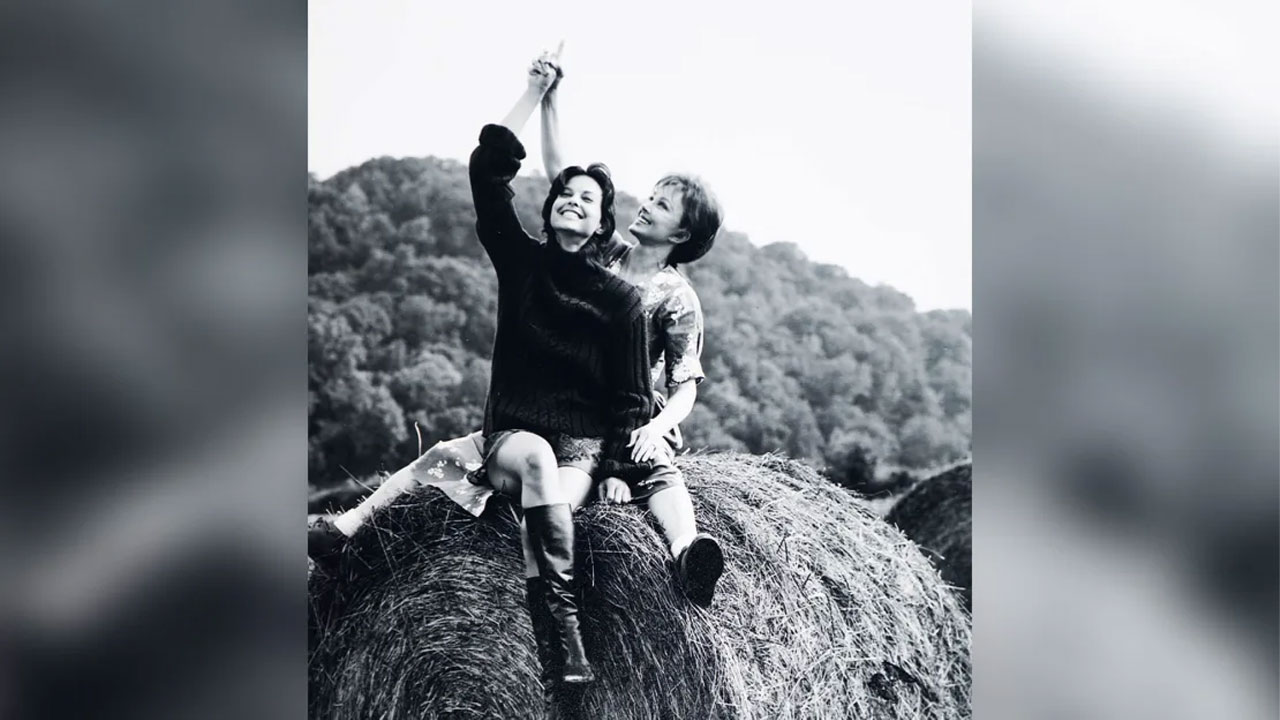

Judd said she is still grieving her mom but in different ways now. She smiles when she finds a folded Kleenex left in one of her mother’s pockets and feels her spirit in family traditions, like playing charades over the holidays.

“I think we all deserve to be remembered for how we lived, and how we died is simply part of a bigger story,” Judd reflected.

She remembers her mom living with a great sense of curiosity.

“My mom is now in the vastness of consciousness in the mind of God. What a great place for her to be,” Judd said. “All of these mysteries which just made her daydream are now where her spirit resides.”

She also remembers her mother’s ability to rise from the sofa to greet her, even in the depths of depression, whenever Judd would stop by to visit on the back porch of her mom’s Tennessee home.

“Invariably, she got up. No matter how sick she was,” Judd recalled. “And she would light up. And she would come to the back door and open it. And she would exclaim, ‘There’s my darling, there’s my girl, there’s my baby!’ And that’s how I see my mom.”

The second season of “All There Is” is available now wherever you get your podcasts.

Stream the best of Fiji on VITI+. Anytime. Anywhere.