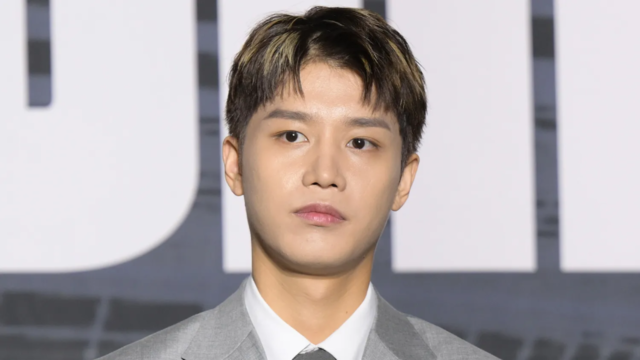

Abu Ala' has buried his teenage daughter and son. [Source: BBC News]

The tents are so close to the border wall between Syria and Turkey, they are almost touching it.

Those living here on the Syrian side may have been displaced by the country’s more than decade-old civil war. But they could also be survivors of the earthquake. Catastrophes overlap in Syria.

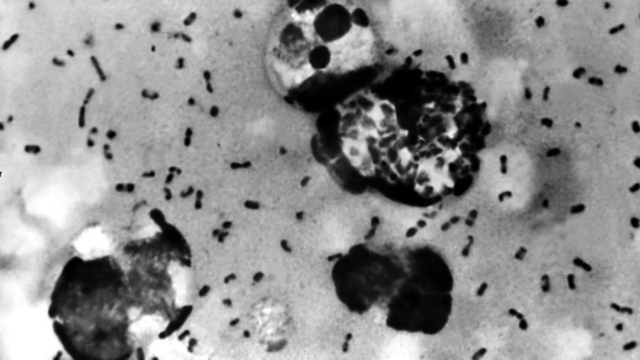

The earthquake, untroubled by international borders, has brought havoc to both countries. But the international relief effort has been thwarted by checkpoints. In southern Turkey, thousands of rescue workers with heavy lifting gear, paramedics and sniffer dogs have jammed the streets, and are still working to find survivors. In this part of opposition-held north-west Syria, none of this is going on.

I had just crossed the border from four days in the city of Antakya, Turkey, where the aid response is a cacophony – ambulance sirens blare all night long, dozens of earth movers roar and rip apart concrete 24 hours a day. Among the olive groves in the village of Bsania, in Syria’s Idlib province, there’s mostly silence.

The homes in this border area were newly built. Now more than 100 have gone, turned to aggregate and a ghostly white dust which gusts across the farmland. As I climb over the chalky remains of the village, I spot a gap in the ruin. Inside, a pink-tiled bathroom sits perfectly preserved.

The earthquake swallowed Abu Ala’s home, and claimed the lives of two of his children.

In the dark, he and his wife clung to olive trees as aftershocks rocked the hillside.

The Syrian Civil Defence Force – also known as the White Helmets – which operates in opposition-held areas, did what they could with pickaxes and crowbars. The rescuers, who receive funding from the British government, lack modern rescue equipment.

Abu Ala’ breaks down when he describes the search for his missing 13-year-old son, Ala’. “We kept digging until evening the next day. May God give strength to those men. They went through hell to dig my boy up.”

He buried the boy next to his sister.

Bsania wasn’t much, but it was home. Rows of modern apartment buildings, with balconies facing out across the Syrian countryside into Turkey. Abu Ala’ describes it as a thriving community. “We had nice neighbours, nice people. [They] are dead now.”

As we leave, he asks me if I have a tent. But we have nothing to give him.

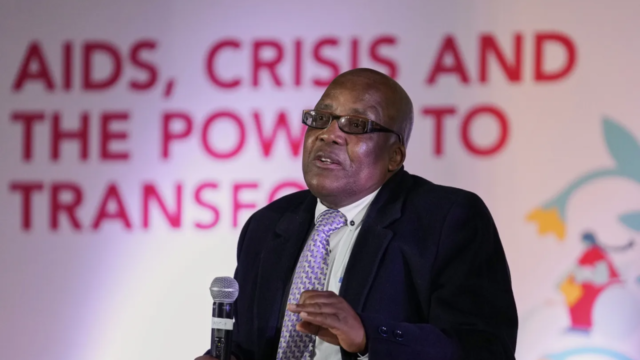

I meet up with the White Helmets, expecting to find them looking for survivors. But it is too late. Ismail al Abdullah, is weary from effort, and what he describes as the world’s disregard for the Syrian people. He says the international community has blood on its hands.

Apart from a few Spanish doctors, no international aid teams have reached this part of Syria. It is an enclave of resistance from Bashar al-Assad’s rule. Under Turkish protection, it is controlled by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), an Islamist group that was once affiliated to al-Qaeda. The group has cut those links, but almost all governments have no relations with them. For our entire time in Syria, armed men, who didn’t want to be filmed, accompanied us and stood at a distance.

More than a decade into Syria’s stalled civil war, the 1.7m people who live in this area continue to oppose President Assad’s rule. They live in makeshift camps and newly built shelters. Most have been displaced more than once, so life here was already very hard before the earthquake.

The international help that reaches this part of Syria is tiny. Many of the earthquake victims were taken to the Bab al-Hawa hospital, which is supported by the Syrian American Medical Society. They treated 350 patients in the immediate aftermath, general surgeon Dr Farouk al Omar tells me, all with only one ultrasound.

When I ask him about international aid, he shakes his head, and laughs. “We cannot talk more about this topic. We spoke about that a lot. And nothing happened. Even in a normal situation, we don’t have enough medical staff. And just imagine what it’s like in this catastrophe after earthquake,” he says.

At the end of the corridor, a tiny baby lies in an incubator. Mohammad Ghayyath Rajab’s skull is bruised and bandaged, and his small chest rises and falls thanks to a respirator. Doctors can’t be sure, but they think he’s around three months old. Both of his parents were killed in the earthquake, and a neighbour found him crying alone in the dark in the rubble of his home.

The Syrian people have been forsaken many times, and tell me they have grown used to being disregarded. But still there is anger that more help is not forthcoming.

In the town of Harem, Fadel Ghadab lost his aunt and cousin.

“How is it possible that the UN has sent a mere 14 trucks worth of aid?” he asks. “We’ve received nothing here. People are in the streets.”

More aid has made it into Syria, but not much and it is too little, too late.

In the absence of international rescue teams in Harem, children remove rubble. A man and two boys use a car-jack to prize apart the collapsed remains of a building, carefully salvaging animal feed onto a blanket. Life isn’t cheaper in Syria, but it is more precarious.

The day is ending and I have to leave. I cross the border back into Turkey and soon get stuck in a traffic jam or ambulances, construction equipment – the gridlock of a national and international aid response.

My phone pings with a message from a Turkish rescuer telling me his team found a woman alive after 132 hours buried under her home. Behind me in Syria, as darkness falls, there is only silence.

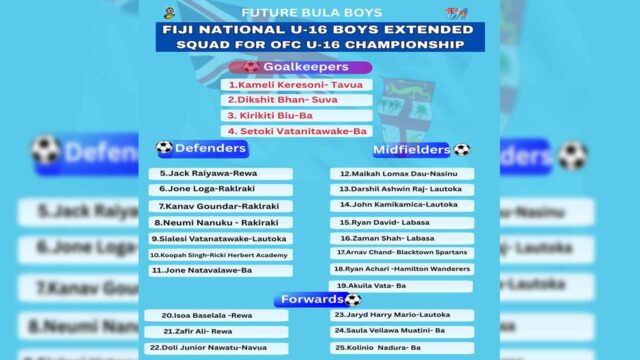

Stream the best of Fiji on VITI+. Anytime. Anywhere.