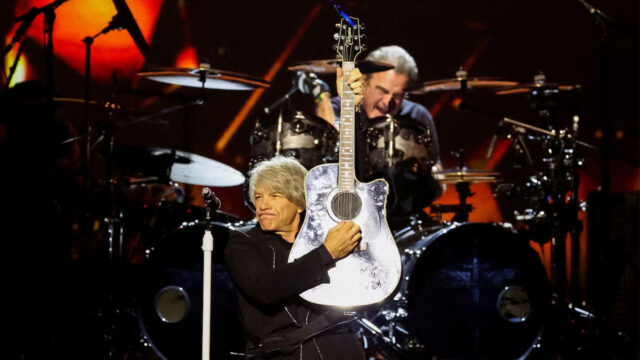

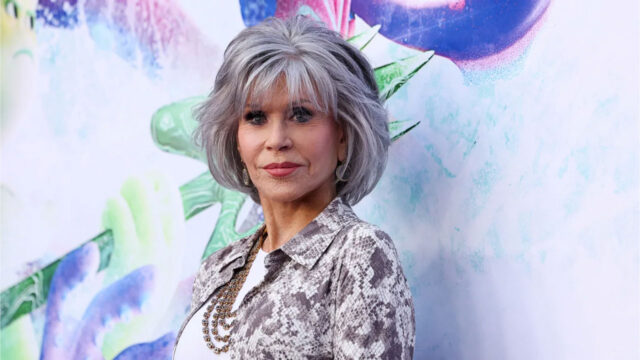

A student protest at China's top university on Sunday. [Photo: BBC News]

In China last weekend, a new generation emerged; many taking part in their first-ever public protest.

On the streets, they demanded a release from a zero-COVID policy that has been in force for nearly three years.

In Shanghai, protesters had been quiet at first. They had gathered to pay tribute to victims of an apartment block fire in the western Xinjiang region. Many believed Covid measures had prevented escape from the flames.

So under a heavy police guard, they grieved. They held up blank papers in protest, laid flowers, and remained silent.

Then some began to shout: “Freedom! We want freedom! End lockdowns!”

As the night wore on, the crowd grew bigger and bolder. At 03:00 local time early on Sunday (19:00 GMT on Saturday), they chanted: “Xi Jinping, step down! Xi Jinping, step down!”

One participant in his early twenties said he’d run onto the street after hearing the crowd from his room.

“I have seen many, many people angry online but nobody had ever stood out on the street to make a protest,” he told the BBC.

He’d brought his camera to record what he felt were historic events. “I see many people – the policeman, the student, the old people, the foreigners. They have their different opinions but at least they can speak out.

“It’s meaningful to have this assembly. I feel this will be a precious memory for me.”

A young woman on the edge of the crowd said she found it a thrilling but fragile moment. “I have never seen anything like this in my life in China,” she told the BBC.

“I feel like a relief. Finally, we can get together, and gather around – to say something we have wanted to say for a long time.”

Zero COVID had stolen the best years of their lives, she said. Her generation had lost income and livelihoods, opportunities for education and travel. Trapped in lockdown for months at times, they’d been separated from family and delayed or cancelled life plans.

They were “angry, sad, helpless” – in a state of purgatory.

Similar calls were heard in several major cities across the country that weekend. At the elite Tsinghua University in Beijing, students inspired by demonstrations they’d seen online also assembled.

A video – now viral – showed a girl speaking rapidly, fearfully, into a loudspeaker. At times her voice breaks and she’s in tears. But the crowd carries her: “Don’t be afraid! Go on!” they say.

“If we don’t speak up because we’re afraid of being discredited, I think our people would be disappointed in us,” she says hoarsely. “As a student of Tsinghua University, I would regret it forever.”

For older observers, the political demonstrations – a sight not seen in decades – sparked memories of the 1989 protests in Tiananmen Square, also led by students who called for a more free China.

But some say this generation’s zeal comes from them not knowing how those protests ended – in a bloody crackdown.

“The combination of youthful idealism – fearlessness without the burden of painful memory – means young people are taking to the street and demanding their rights,” says Human Rights Watch’s China researcher Yaqiu Wang.

Others argue that sells the protesters short. Their youth belies just how attuned they are to the Chinese system and its rules, says Wen-ti Sung, a political scientist at the Australian National University.

He’s marvelled at their “tactical savvy”. The young protesters today “are the best-educated generation China has seen”, he says.

“They know the red lines. They’re trying to push the envelope without breaking it,” he says.

The protesters in Shanghai shouted their calls for Xi’s removal. But at almost every other rally, demonstrators tamped down demands they feared were too political.

Blank paper – devoid of incriminating scrawls – became their symbol. When told by police to stop calls to end zero COVID, they responded sarcastically, chanting for more testing and more restrictions.

“Just watch how carefully they pre-emptively try to cover all the bases to minimise accusations that the Chinese government can make against them,” Mr Sung says.

Protesters were also alert to voices subverting their message.

In Beijing, when one man warned of “foreign influences”, he was mocked by others who shouted: “By foreign influence, do you mean Marx and Engels? Is it Stalin? Is it Lenin?”

The Chinese Communist Party cites Marxism as its guiding ideology.

The Beijing crowd pressed on: “Was it foreign forces who started the fire in Xinjiang? Was it foreign forces who overturned the bus in Guizhou?”

“Was it foreign forces who drew everyone out here tonight?” one man cried to the crowd. It roared back: “No!”

Prior to the pandemic, young Chinese had mostly been content with their future prospects. Covid changed all that, imposing restrictions and stunting the economy.

“I cannot travel around the world, I cannot see my family,” the young man with the camera in Shanghai said. He told the BBC he feared for his mother, who has cancer, in the southern city of Guangzhou. City officials lifted Covid restrictions in most of its districts on Wednesday.

“I really want to see her. For a long time now, I didn’t see her, didn’t touch her face, didn’t have dinner with her,” he said. “I hope this lockdown policy will be released. As soon as possible.”

He was detained later that day by police, the BBC was later told.

Many who spoke to the BBC or are seen speaking in footage online say they want to see their country progress.

At the protests, crowds sang China’s national anthem over and over again – particularly the swelling chorus which urges people to “Stand up! Stand up! Stand up!” and defend their country.

One way in which this generation really is different is their fierce patriotism, having grown up in the era of China’s rise, says Mr Sung.

He labels many of them “liberal nationalists” – who, in believing so fiercely in the system, demand accountability when it fails.

“Sentiment can switch from pro-government to anti-establishment really quickly,” he says.

But there remains a collective desire to prove their protests are legitimate and on the right side of the law.

In the Tsinghua campus video, after the speaker raises concerns the protest could be appropriated by troublemakers, the crowd cried out “No lawbreakers here! No lawbreakers here!”

A male voice is then heard, worried: “If we lose control of this, then we’ll have really lost.”

“We don’t have experience doing this… but we’ll slowly work this out.”